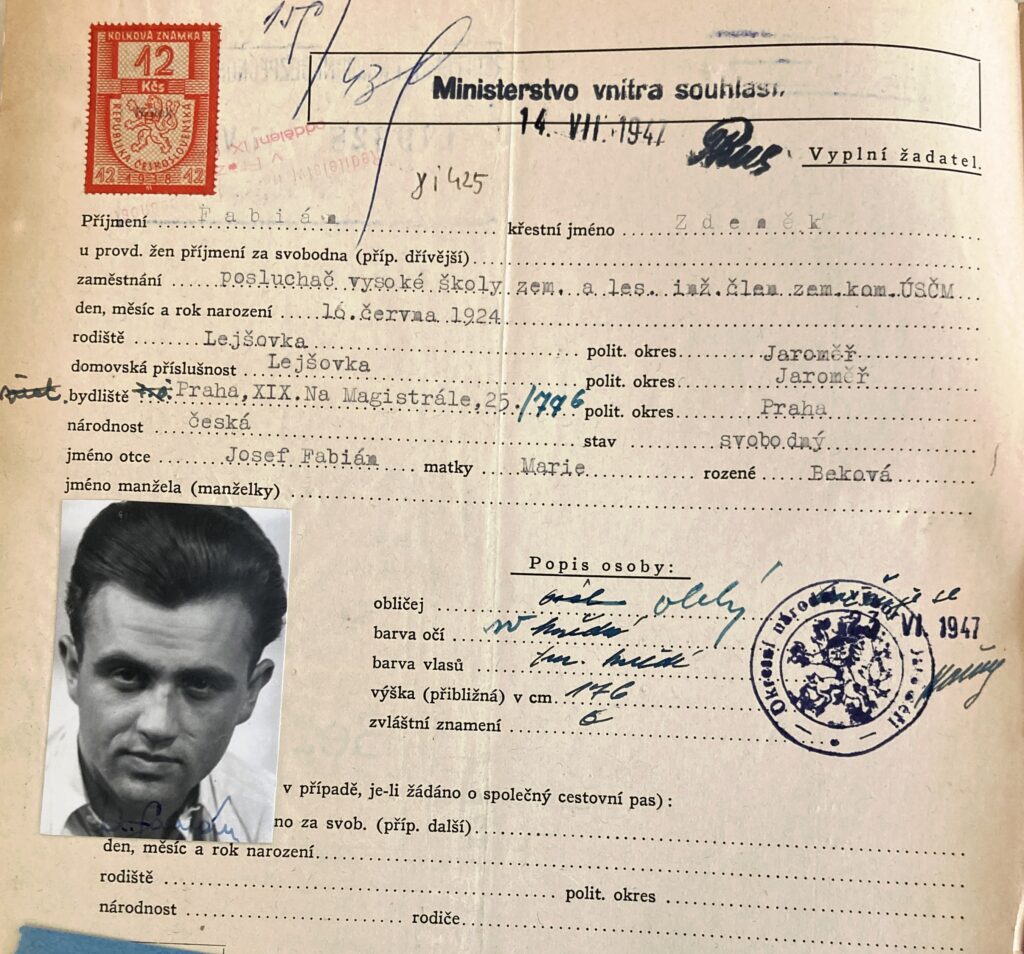

Zdeněk Fabián

My life began in the village of Lejšovka near Hradec Králové. Here I attended the municipal school, in the building of which my grandfather Václav Fabián, then mayor of the village, participated. I completed my primary education in 1939 in Josefov. I spent my childhood and boyhood on a farm. I have beautiful memories of my mother, Maria, née Beková from Libřice, who was able to devote the most time to me and my siblings Jiřina, Josef and Květa. I was raised to respect other people and to be patriotic. From this distant time, I still have vivid memories of how cakes were baked during pilgrimages and feasts, and above all how demanding the physical work on the farm was, especially during the harvest. Our farm also included a forest and in the winter we went to cut down trees, even when there was a lot of snow.

I completed my secondary education at the Agricultural School in Chrudim, where I graduated in 1944. After that, I was supposed to dig trenches and was threatened with being sent to forced labour in the Reich. I chose the job of a teacher and taught in Sobotka for a while. During the war, I was also actively involved in the illegal resistance movement of the Czechoslovak Youth. I became the regional leader of the organization in North-Eastern Bohemia. I received a written authorization with instructions for resistance activities, two ID cards and came into contact with the underground movement in Prague. Much later, I did realize how dangerous it all was and what could follow if we were betrayed. After the war, universities were reopened. I applied to study at the Czech Technical University in Prague and between 1945-48, I studied agricultural and forestry engineering there. I finished my studies with a practical and theoretical exam in mid-June 1948. At that time I also married Hana Pácová, a law student at Charles University. The wedding was secret, in a private apartment, without my parents’ knowledge.

The journey was very strenuous. We crossed at night, holding hands for fear

The political development in the Czechoslovak Republic after the war was completely contrary to my thinking. Especially after the Communist takeover in February 1948. In the summer, my wife and a group of friends decided to cross the border in the Šumava Mountains. We arrived at the hotel and, as agreed, handed over our suitcases with personal belongings to a horse-drawn carriage that was supposed to transport them separately. We were unlucky here, because we never saw the suitcases again. We returned to Český Brod and after about a week tried to cross the border again. The journey was very strenuous. We crossed at night, holding hands for fear that one of us would get lost in the dark. We made it. We got to the American sector in Nuremberg, where we were accommodated in the Czechoslovak camp Goetheschule. This is where my life journey beyond the borders of home begins.

After obtaining necessary documents, we reached Paris. From there, in 1949, we traveled to Madagascar, where many refugees from Eastern Europe were being concentrated at that time, so we met Hungarians, Poles and members of other nationalities. Our daughter Nora was born. Here I also suffered from malaria, after which I was very weak. I met a Czech who had left for the USA after World War I. Before that, he had worked in the Škoda Pilsen company as a tool designer. When the Germans were building their largest war cannon, the so-called Big Bertha (Dicke Bertha), he had to advise the Krupp plants on how to create a thread in the barrel. It was not easy to cut it in such a large barrel and temper it.

Our Madagascar adventure ended in 1952, when we returned to Paris. I was politically active in the exile Agrarian Party there and spoke on the radio several times during broadcasts to Czechoslovakia. After staying for more than a year, we traveled to New York, where I worked at the Chilean consulate for about a year and a half. Our son Peter was born in 1955. I received an offer in South Bend, Indiana, from the Oliver company, where I could have applied my engineering education for the first time. The company had two factories with a total of 6,000 employees and focused on the production of agricultural machinery. From there I moved to Lincoln, Missouri, where they produced special pumps and lubricants for cars. I worked there until 1963, when the company opened a branch in Brussels and I became its representative. Our family life continued again in Europe. After some time, the company’s branch moved to Leidschendam, a suburb of The Hague in the Netherlands, where we remained until 1972. During this period, a family tragedy occurred when my wife Hana died in 1965 after a sudden stroke. I traveled all over Europe with the company. We introduced new production methods and procedures, for example, using special adhesives instead of welding.

My second wife, Elza née Rátzová, graduated in 1954 from the rubber department in Zlín, then Gottwaldov. With her knowledge of German and English, she was employed in Bratislava at the Matador company. Her path to permanent residence abroad was also very dramatic. When conditions in Czechoslovakia were partially relaxed during the Prague Spring, the possibility of traveling to Western countries also opened up. She visited her cousin in Geneva, stopped by the Swedish consulate, applied for visas and then permanently moved to Stockholm. She worked for the rubber company Trelleborg, where we met.

In 1973, I already had enough production and technological experience and also created a background for my own business. I founded the company FEO Engineering in Emmerich am Rhein, West Germany, not far from the Dutch border. In 1981, I moved it to Siegburg near Bonn. Elsa and I bought a family house in Neunkirchen and then an apartment in Bonn, where we still live today.

I was afraid to go to Czechoslovakia because in the 1950s, I was sentenced to a long prison term for anti-communist activities and desertion

My first trip behind the Iron Curtain took place in 1970 to Budapest. The regime there was milder. I took out insurance for a thousand dollars in case I had problems returning to Germany. I was afraid to go to Czechoslovakia because in the 1950s, I was sentenced to a long prison term for anti-communist activities and desertion. But I closely followed the political situation there, and especially the possibilities of establishing business contacts. Much later, my business partner Mr. Gábor from Holland and I made our first business trip to South Bohemia. We presented a device for fogging cherry orchards against freezing, controlling temperature and humidity with the help of satellites. We expanded our offers to Moravia as well. With the American company Johnson, we introduced lines for growing tomatoes, harvesting peas, sweet corn and new ways of harvesting some types of fruit. We were also in contact with František Čuba at the agricultural complex Slušovice. This company was very progressive in introducing new technologies. I realized, especially in the beginning, that I was being watched by State Security officers during these visits. I came into contact with managers of foreign trade companies such as Motokov and Transakta, whom I even sometimes accompanied on trips to the USA. I remember well how they were amazed at the living conditions there. At home, until then, they had only heard about poverty, unemployment and strikes. That was their misconception of America. I never met some of them again after returning to the aforementioned companies. They made a mistake and apparently spoke truthfully about what they had seen overseas.

As you can see, my life path was far from easy. I came to a foreign country empty-handed. It was challenging to start over. However, I was given a helping hand right from the start, because the West saw what was happening in Czechoslovakia. Since childhood, I have learned at home that most work in agriculture is physically very demanding, so I was interested in all possibilities of making it easier and mechanizing. I was raised at home to be truthful, have a sense of justice and be patriotic. That is why I joined the resistance against Nazism and later Communism. I got to know a large part of the world and thanks to my tenacity I worked my way up to knowledge of modern technology and its application in many fields, especially in agriculture. Today, having reached such a blessed age, I feel great satisfaction that I can once again meet with relatives and friends in my free homeland. Even though I have spent most of my life abroad, this is where I came from, this is my home.

Zdeněk Fabián passed away in Bonn on July 18, 2018 at the age of ninety-four.