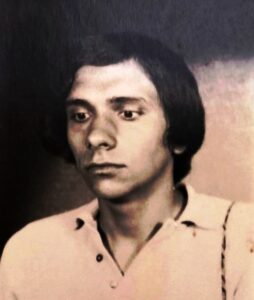

Tomáš Mertl

I was born on April 25, 1949, in Havlíčkův Brod. My father was a doctor, mother a housewife, later she worked as a clerk. Let´s move forward some twenty years later, to Piazza Navonna in the center of Rome. We sat there on the steps under the fountain with our friend Pietro, a hairy philosophy student, and watched the crowds of tourists, café tables, and sellers of paintings and souvenirs. He asked me the fateful question: Do you think the Soviets will send tanks to Czechoslovakia? It was shortly before midnight, but the square was alive as in broad daylight. The date at the time could have been seen on the newspaper poking out of the pocket of Pietro’s corduroy jacket: August 20, 1968.

It was enough to say that we were from Czechoslovakia, people immediately answered us with ``Dubček``

My three friends and I left Prague for a 14-day trip to Italy just a week before. It all started when Hugo, one of the participants in our expedition, procured a fake invitation to Italy, and the rest, namely the procurement of a travel clause, an Austrian and Italian visa and, of course, a foreign exchange promise, were almost formalities in the euphoric time of the Prague Spring. Equipped with a sleeping bag, a return ticket from Prague to Venice and endless optimism, we set off on our pilgrimage by hitchhiking through the unknown, but attractive and friendly, Italian shoe peninsula. It was enough to say that we were from Czechoslovakia, people immediately answered us with “Dubček” and expressed their sympathy with “socialism with a human face”, in which mainly young people, traditionally inclined to leftist ideals, saw a kind of third way. They asked us questions about fundamental things that testified to their political maturity, while we, inexperienced rookies raised by Communist youth organizations, were unable to give satisfactory answers. We had arrived in Rome the day before, spent the night on benches in a park in front of a church, and spent the following day by exploring the eternal city. Tired of the heat, dust and noise in the evening, when we discovered the almost divine calm and bohemian atmosphere of Piazza Navonna, we felt wonderful. We met Pietro and his friends when we were looking for information about cheap hostels. A high school diploma in English and a trip to England the previous summer helped me to gain some self-confidence, so I wasn’t shy about addressing strangers in English. I was extremely lucky with Pietro. Not only did he speak excellent English, but after a few minutes of conversation he spontaneously offered us a night in his student apartment. That was a big deal: after a week of traveling in tiny Fiat cars, sleeping at beaches, parks and railway stations, bathing in salt water and washing in unattractive public toilets, we now had the prospect of not only a comfortable bed, but also a refreshing shower! And most of all, it didn’t cost us a single lira.

Pietro’s question about Soviet tanks caught us by surprise. We didn’t even think about such an eventuality. I replied sovereignly: they wouldn’t dare! That evening we lay snuggled up in wonderfully comfortable beds. But the night was short. A few hours later, we were awakened by a banging on the door. Pietro and other people waved the morning newspapers in front of our eyes with big headlines: Russians in Prague. We hadn’t woken up properly yet and we were already on our way to some local newspaper, where journalists showed us photos and told us shocking details of the occupation. We had a crazy day. We were dragged from newsroom to newsroom, from studio to studio, journalists, editors, and photographers used us as an information source, our only reward was a few sandwiches and bottles of beer. But we got to know other Czechs and Slovaks who were in Rome at the same time. We exchanged information and planned what to do next.

Some did not hesitate and asked for emigration to the United States, Canada or Australia, others wanted to return to Czechoslovakia as soon as possible, even though the situation was highly uncertain. We decided to go first to Vienna, from where, as we hoped, further developments could be better estimated. After spending a few days in a huge gymnasium in Vienna, which was visited daily by American recruiters offering quick and easy emigration to the U.S. with the lure of early citizenship, which was, however, also associated with the risk of being deployed to the Vietnam War, two of my friends decided to return. Some nice Australian lady drew me to move to her country, but I didn’t want to move too far away from Central Europe, although I obviously didn’t want to go back to listen to the lectures on Marxism and Leninism. When I heard that the Swiss would grant a visa for three months, during which one could decide whether to stay and apply for asylum or go somewhere else, I did not hesitate and immediately went to join the long queue outside the Swiss embassy. Unsightly scenes took place there. Rumors were spreading the Swiss would not accept more than 10,000 Czechoslovak refugees. Some applicants were afraid that they wouldn’t be able to get there in time, they overwhelmed the queue, pushed forward, and slaps and disgusting insults were also present, some people waiting in the crowd even fell to the ground and screamed, the embassy employees probably wondered who they were inviting to their country. The most hardened ones spent the whole night in front of the building and thus proved who was the best front-line fighter.

Three months passed, and I still could not decide

At the end, there was enough space for everyone, including me, so in early September I arrived on a special Red Cross train to the Swiss border town of Buchs, where we passed a medical check and continued to the refugee camps. I was sent to a village near Zurich, from where I soon left for the picturesque city of Fribourg, where preparatory courses for university studies were held for new immigrants. Three months passed, and I still could not decide whether or not to apply for political asylum, which was granted to Czechoslovak citizens very easily, almost automatically, given the situation. The deadline for a decision was extended by three months, but at the end of March 1969 I had to make a final decision. It wasn’t easy. My mother used to send me typically motherly letters about how she longed for me to come back. But then, just on time, the first letter from my father came, devoid of any emotion. He wrote to me that I was old enough to decide for myself, and if I wanted to stay, he would send me everything necessary, mainly various documents. This helped me a lot, and the very next day I applied for asylum, which I received immediately. That same evening, I went to a pub with couple of friends, we drank Swiss beer to seal my exile fate. It was a month before my twentieth birthday and twenty-one years before my next visit to Czechoslovakia.

I got my Master’s Degree in Slavonic and English studies at the University of Fribourg.

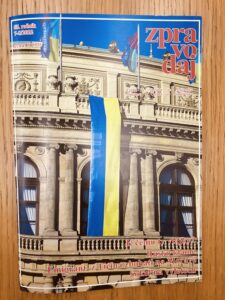

I worked successively for three embassies in Berne as a translator, later as an immigration, administrative and consular officer. I got married in 1980 (now I have two adult children), three years later I got Swiss citizenship. I have always tried to maintain contact with the local Czech community, and since January 2019, I have been the editor of the monthly Zpravodaj (Reporter), the official organ of the Union of Czech and Slovak Associations in Switzerland.