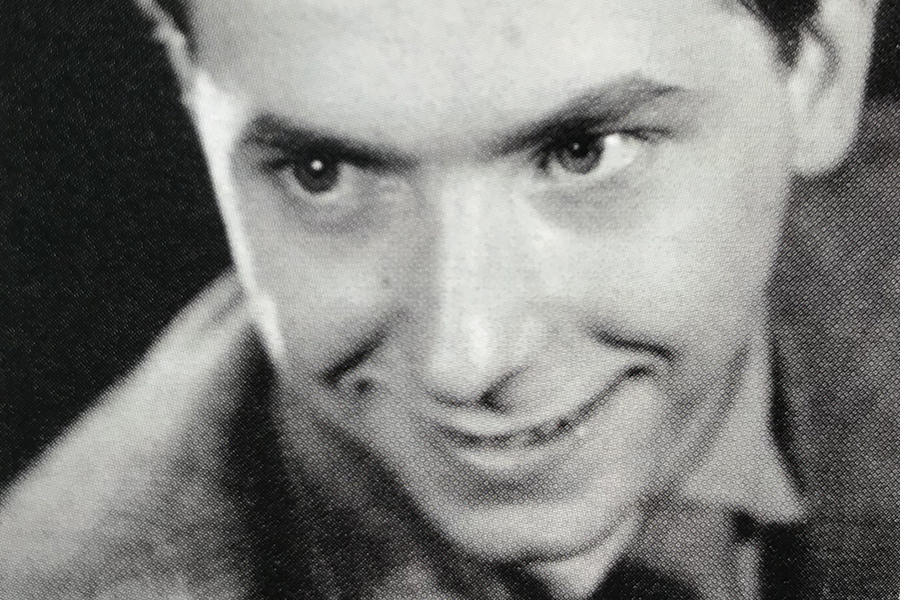

Paul Ort

The communist regime seemed to be at the height of its power when I graduated from the Charles University’s Faculty of Medicine in 1961. The path to my graduation was by no means a straight line. When I was fifteen years old, the party decided I couldn’t continue my studies. They didn’t mean to punish me (I actually welcomed the news with the enthusiasm of youth), they were punishing my father. They found him too bourgeois – he was a doctor, a surgeon in Prague.

My step-mother arranged a job position for me in a chemical plant Spolana Neratovice. There I received my “re-education” to become a working class cadre and I was able to enrol in secondary school in Nymburg and, after three years, start studying medicine in Prague. After graduation, a job was assigned to me in a department of orthopaedics in a hospital in Teplice. When the opportunity to go to Tunisia as a tourist came up, the head physician asked to talk to me and said: “See that you don’t forget to come back to us, Pavel!” And I remember replying: “How could I possibly sir, now, when I got a raise?” I was recently awarded fifty extra crowns and my new monthly wage came up to 950 Czechoslovak crowns (around 44 of today’s dollars).

I spent three more months in Tunisia. Two more Czechs escaped from Pobuda, independently of each other. Authorities granted all of us political asylums, we even received documents that served as passports. It was quite a generous gesture for such a poor country.

Four hundred of us Czech people boarded the Russian ship Pobuda in Odessa. There must have been cops as well, mingling with the tourists. On the last day of the trip, they took us to a beach near Tunisia. I seized the opportunity and made a break for it. I sneaked off only wearing my trousers, I was too afraid to carry anything else. Only my swimsuit I put in my pocket – a souvenir. Not far from the beach I flagged down a car which took me to a city.

People from West Germany helped me a lot back then in Tunisia. I felt like it was a partial compensation for the Nazis having killed my mother when I was only six years old. A cultural attaché who has been looking after me asked me if I wanted to go back to the dock. Pubuda was leaving that evening. A resolute “No!” was my answer – and that’s how I gained my freedom.

I spent three more months in Tunisia. Two more Czechs escaped from Pobuda, independently of each other. Authorities granted all of us political asylums, we even received documents that served as passports. It was quite a generous gesture for such a poor country. I often ponder if my home country would have treated refugees with similar generosity. When I decided to immigrate to the US, Americans also provided me with accommodation and food. Simply put, there were always people willing to selflessly help me.

I knew I had distant relatives in Venezuela and so I set off again. I found a job as a doctor accompanying a geographic expedition which determines the Venezuela-Brazil border every year. The border is defined by the water divide of the Orinoco and Amazon rivers – if the water travels to the Orinoco, the land is claimed by Venezuela while Brazil gets the area where the rivers flow into the Amazon. We had to travel vast distances through a thick jungle. Local doctors refused to take part in these expeditions so I was able to make good money in one season. The high-quality education I received in Prague helped prepare me for this experience. I even put into use my basic knowledge of teeth pulling.

I came back to the States and started to build my career in medicine. I passed an exam validating the education I received while in Czechoslovakia and trained for six years as a surgeon and an orthopaedist. I was lucky to study at the New York University (NYU) and to work there, as well as at the renowned Bellevue Hospital. I went on to open a private practice at the university. I was also building an academic career. It helped both of my careers a lot that I was present when a new method for operational treatment of hip fractures was created. We travelled a good part of the world giving lectures on this treatment, including South America and Europe. I eventually achieved the title of Clinical Professor of Orthopaedic Surgery at the NYU.

I was in private practice for a total of 35 years. When I was going to retire, I was offered a job as a chief physician at VA Medical Centre in Manhattan. I’ve been working here for thirteen years. I very much enjoy talking to medical students who want to specialize in orthopaedics. And they enjoy coming with me to Bohémka – a Czech garden restaurant. Apart from sport, learning and talking to the young generation is what keeps me in a good shape.

I came back to the States and started to build my career in medicine. I passed an exam validating the education I received while in Czechoslovakia and trained for six years as a surgeon and an orthopaedist. I was lucky to study at the New York University (NYU) and to work there, as well as at the renowned Bellevue Hospital.

Finally, I want to say that communists actually did me a favor when they forced me out of my home country. It wasn’t easy to leave; I had to overcome various challenges and adverse circumstances. But I had interesting adventures. And that’s definitely a better way to spend a life than to live in a totalitarian regime. That just wasn’t for me.

This article is based on an essay sent to us by Paul Ort.