Kateřina Fuchs

I was born on May 16, 1921 in Vienna. Both my parents came from Bohemia. My father, Vilém Neumann, was born in Křivsoudov in Benešov region and came to Vienna after the end of World War I. My mother, Kamila was born in Klučenice near Příbram, and was sent to attend school in Vienna. They married in 1920. My father opened a shop and dealt in construction steel, and my mother worked with him as an accountant. After the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy, my parents “opted” for Czechoslovak citizenship. We lived in Vienna as “foreigners”, which never came to my mind. While at home we spoke a good bit of Czech, we went to German schools. My father was a great athlete and sportsman. In his youth in Bohemia, he was a bicycle racer and he had a metal box with many medals awarded to him for races he won. In Vienna, he was a member of an athletic and sports club. My mother loved music and was a good pianist.

My father’s ironmonger business flourished in the 1920s. Together with my parents and my younger siblings, sister Alice and brother Oswald, we lived in a large flat, had a cook and a governess. I know these “good old times” only from hearsay. I was too young then. Then came the 1930s. The theme of my parents’ conversation concerned such matters as “debts, settlements and bankruptcies”, announced by the daily press. Everybody seemed to be losing money. This period remained in my mind most vividly. Queues of unemployed stood in front of Employment Offices. There were some riots and unrest, first dead and wounded, Chancellor Dollfuss was murdered and then came the “Anschluss”. German troops marched along the Ring (Vienna’s main Circular Avenue). The Viennese were jubilant.

To date, I´m obliged to my teachers who gave me a balanced general education

After finishing elementary school, I attended a Gymnasium (Grammar school). There I took Latin as of the 5th grade. I learned a lot and got along well with my schoolmates. To date, I´m obliged to my teachers who gave me a balanced general education. We also had gymnastics, played youth games and attended ski courses. I took part in these activities with pleasure.

Our family was Jewish. We had religious instruction at school. On Jewish holidays, my parents went to a house of prayer. My father knew how to read Hebrew, and my mother had an open prayer book on which was written:” Prayers for Women”, but she apparently did not know what was going on at the Torah. On these occasions, we children had school holidays. After the Dollfuss Party came to power, we were obliged to attend religious services for young people at the nearest Synagogue on Saturday afternoons, where we received a prayer sheet, which we then had to hand in at school. There was also some singing there. Boys and girls had to sit on opposite sides. As a matter of fact, at that time I registered no hatred or jealousy from my Christian schoolmates. Perhaps this was only my one-sided view.

On the next day after the Anschluss, Jewish girls were seated in the last rows at school. A Nazi badge-wearing trustee was assigned to my father’s shop. He then accompanied my father on every step. Austria became the “Ostmark” (East Mark). After the end of the school year, my parents sent my sister and me to relatives in Bohemia. We landed in Bohemia like a bird which fell out of its nest. Everything turned out to be different. A little adventure and mainly my youth allowed me to comprehend and withstand many things, but I also “matured” prematurely, struggling to be able to care for my sister and myself.

For the time being” they remained with my little brother in Vienna. He fell ill with diphtheria but as a Jew was not admitted to any hospital infectious-disease unit. My mother had to care for him at home. My parents were thrown out of their flat and had to sublet a room from a Jewish couple. According to information obtained from the Jewish Religious Community, which I looked up in Prague after the war, my parents and brother were transported to Minsk on November 28, 1941. My sister and I stayed with our grandmother and aunt in Milevsko, then in Žatec with my father’s brother Rudolf and my mother’s cousin Emma in Pilsen. I was supposed to finish my secondary education, but after the occupation of the Sudetenland everything was different again, because my relatives fled to Prague.

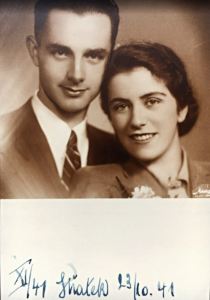

Based on an advertisement I landed the position of a governess with a family living in the Krč district of Prague. I possessed absolutely no qualification for performing satisfactorily. I spoke Czech only partially, and did not master it verbally or in writing. I was 17 years old, a “spoiled young lady”, with no knowledge of world affairs and mainly not used to serving others. The children were unruly and knew how to take advantage of my inexperience. After several months, I was given notice. A second job in the Prague district of Dejvice ended just as badly. Therefore, I decided to give private language lessons. First, I found myself one-room lodgings and mainly a family where I was to teach the mother, son and daughter German and English. As a seamstress, I learned to sew to possibly keep myself with that craft. I begged her to take me on as an apprentice, which she did. My sister still lived in Milevsko. In the meantime, Germany occupied the rest of Czechoslovakia and the racial Nuremberg Laws were introduced in full force. For some time, I lived in a boarding house, which also cooked lunches for its guests. There I met a youth movement known under the name of El Al for Czech youths, who as Jews were already banned from other communities. They accepted me and in the summer groups were organized for work in the countryside. These were known as Hakscharahs and their program was preparation for life in what was then Palestine. There I also met my future husband, Jan (Honza) Fuchs. Thus far, my language classes managed to maintain me financially. However, I neglected any attempt to get out of the country when it was still possible. Honza and I were already married. The wedding took place at the town council assigned to Jews in the Smíchov district of Prague.

However, in the Autumn of 1941, transports to the concentration camps began. Me and Honza had to separate for a long time. I ended up in Terezín for three years, then briefly in Auschwitz, after which I was fortunately assigned to a work transport in Freiberg, Saxony, where we were sent to factories. We worked 12 hours a day in two shifts. We could rest only on Sundays. Food consisted of potatoes in some sort of sauce and turnips. Bed bugs and lice in addition to the constant cold bothered us no end. We were very poorly dressed. I had a blue dress with short sleeves and over this a cloth jacket and wooden clogs. On the inner side, under a button, I fixed my wedding ring.

They dressed him in an American uniform, and he drove in a Jeep as a forward party to Pilsen

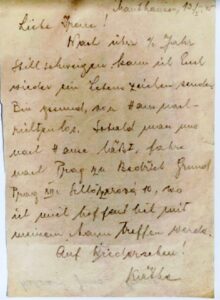

The war theatre came ever closer to us. That we knew. After about four months we received an evacuation order. There was a long roll call and then we were marched in rows of five into freight cars. We travelled for a long period through the countryside without any food. Here and there the train stopped and we could “disembark” to take care of our personal needs. Our travel ended in Mauthausen, a concentration camp for men on the Danube River in Austria. Once we were permitted to write a letter. I wrote to my cousin Irene Fischer to let her know that I was still alive and was looking out for Honza.

The war finally ended. An American Jeep came up the hill and a naked prisoner jumped at the soldier to embrace him. The soldier must have been quite stunned. The German leadership of the camp disappeared somewhere. Where? What was to be done next? The Czech political prisoners organized a council to arrange the return of men and women to Prague. Somewhere they found a lorry, and then we continued by rail. Who will be waiting for us Jewesses? Who of our large family survived this inferno? I was extremely lucky. In front of the “Delousing Station:” in Prague’s Vinohrady district a man in an American uniform came towards me. It was Honza. What a great meeting that was! It was just beyond description. According to his story, Honza also came to Auschwitz and was transported to the factory of the Hassag Company in Taucha near Leipzig. As the battlefront came nearer, Honza and his friend managed to escape and hide in a haystack. The American army found them there. Honza landed in a retaining camp for homeless persons. After some time, the American officers were looking for interpreters with a good knowledge of German, English and Czech. Honza responded to this call. They dressed him in an American uniform, and he drove in a Jeep as a forward party to Pilsen where he was assisting the local quartermaster. Later we met in Prague.

Unfortunately, we realized the final solution planned by the Germans did not spare our families. Both our parents, siblings, aunts, uncles did not survive the Nazi hell. Somehow, we started living as if we had been born again. But we could never forget. As if we were left “alone” in the world. And then the children, Peter and Jirka, came along. I also finished my studies and, thanks to my knowledge of languages, worked in international trade. After the war, Honza was given back his machine tool business, but after 1948 he lost it again and had to work in a factory at a lathe. After August 1968, we all left for Great Britain.

The Fuchs settled in Hendon, northwest London, and both made a living in foreign trade and as translators. They made friends with people from all over the world and traveled frequently. Jan died in 1994, Kateřina in 2015.