Jan Otáhal-Měchura

I come from Šardice near Kyjov, but I have lived in Brno since childhood. I graduated from the teacher training institute, but I never pursued the profession of teacher. In 1934, I set up a driving school in my own house in the Komín district of Brno, which I ran and developed until the German occupation, during the war to a limited extent only, and after the liberation I expanded the business again and moved it to new premises at Zelný trh no. 12 in downtown Brno. At first, I worked completely alone with one vehicle, then I hired five employees and purchased three cars and two motorcycles. I equipped the classrooms with the most modern self-made models, so they were one of the best in the republic. I had dozens of clients. At that time, my life with my wife Hedvika was coming to an end, because I fell in love with my secretary Božena Juránková. On March 31, 1948, all the driving schools in Brno were nationalized, and a new director “politically reliable” was appointed. My children Milan and Alena were already adults, and I would not have been allowed to continue my business in the republic, so Božena and I decided to flee to Austria in July.

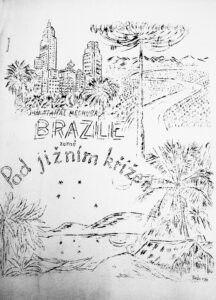

we landed on the Island of Flowers (Ilha das Flores) near Rio de Janeiro, where the main immigrant reception station was located

We spent some three months in a refugee camp in Salzburg before we were accepted into an emigration transport to Brazil. On the last day of December 1948, we landed on the Island of Flowers (Ilha das Flores) near Rio de Janeiro, where the main immigrant reception station was located, similar to the one on Ellis Island in New York. They registered us at the port, gave us old cutlery and cups, and we went to large brick barracks, where no one cared about us anymore. Food was provided in the communal kitchen, and the advertisements on the message boards in the port always showed job seekers what kind of experts were needed at the time.

There was a shortage of technicians, farm workers and medical doctors in Brazil. Božena and I walked around this strange island, full of tall palm trees, exotic bushes and flowers. I bought a few lemons and a pineapple. We ate them for the first time in many years, because such luxury was unthinkable in impoverished Europe. Then we were allowed to take a boat to the mainland. As we were walking the luxurious streets with hundreds of shops in Rio de Janeiro, our heads were spinning with the unprecedented wealth. I bought Božena sardines and chocolate, delicacies we never dreamed of earlier. As we walked through the port, the cleaners were throwing about forty fat hens, which had died in the terrible heat, into the sea. The hens swam in the waves for only a moment, one by one disappearing into the mouths of large predatory fish. We were amazed! Is it possible to waste someone’s property like that here? In our country, people would eat the hens or otherwise use every bit of them. We were simply thinking too much in European thrifty style.

On Sundays we used to go to Catholic services in a chapel on a hill above the sea. The priest spoke beautiful standard German that we all understood. He talked about how four hundred years ago the Portuguese landed in this country and began their work with field masses. The blue sea gently murmured, the blue sky reflected in it, and tears flowed from our eyes. We were all refugees, without a homeland, the whole past was behind us. What would the future be?

The hot, steamy summer was in full swing in December. Down by the sea on the lawns we could hardly breathe, and a pleasant breeze blew on the hill. The food was not expensive, but what I liked most were the bananas and the excellent black coffee, which you can’t get anywhere else in the world. Within three weeks, I got a job in São Paulo as an electrician at a General Motors factory. European workers were welcome at the car industry because they were persistent in their work. When the office assistant led me to the workplace, he pointed out to me that people work slowly in Brazil, so I shouldn’t rush too much. A very strange principle, which I remembered again when I learned that a Czech painter I met had written on the facade of his workshop: “Whoever works a lot in Brazil has no time to earn money.”

Life in South America suited me, but I secretly longed for the USA

Božena and I found a small room in a nearby suburb and began to live our Brazilian dream. Two boys were born to us. Later, I opened my own workshop for repairing electrical components for cars and I also tried farming when we purchased property in the wilderness near the town of Londrina. Life in South America suited me, but I secretly longed for the USA. The dream came true in 1957. We moved to Houston.

Jan Otáhal-Měchura ran a gas station in Texas until his retirement, kept bees, and sold royal jelly to pharmaceutical companies. He died in 1974 at the age of seventy-five. He wrote and self-published a memoir about his time in São Paulo under the title “Brazil – the Land Under the Southern Cross.” His second wife, Božena, who began using the name Beatrix, illustrated the book.