František Jakubec

My story began on March 25, 1916, in a small village called Peklo near Rychnov. A boy, František Joseph Jakubec, was born, who had no idea that his new home would be Rhodesia (Zimbabwe today). I came from a poor family with my mother, a widow, and five other siblings. Each day began with hard work in the fields, meagre food and with no hope of developing a better life.

One day, representatives of the Baťa Organisation came to our village to search for future suitable candidates for the Baťa School of Work. When choosing, they focused on youngsters from peasant and craft families. The Baťa School of Work was designed for students from 14 to 18 years of age who passed psychotechnical exams and health tests. This school gave young boys hope for a quality education, a good job, and a decent wage. The school inspired confidence that everyone would have the same conditions to become successful. It was in their hands how they would take this chance. Each applicant was informed before the job interview that he educates himself in the Baťa’s company mainly by work, both physical and mental. I was used to heavy physical labour, and I did well at our local municipal school. So, I decided to try my luck at the entrance exams at the school, located in Zlín.

Baťa argued that a child from the age of 6 should not receive anything for free

On August 19, 1931, I was admitted to the Baťa School of Work and so at the age of 15, I moved to Zlín, where I spent the next eight years. Thus, a new era of my personal development began. Baťa’s philosophy of education was to teach its pupils independence and financial responsibility. Baťa argued that a child from the age of 6 should not receive anything for free. The aim of the school was to produce a professionally educated specialist so that after graduation he would become a future entrepreneur and manager of the Baťa company. I concluded the so-called “teaching contract” with the company, according to which I had to follow clear rules in the school, dormitory and company. The contract also included a preset salary for tasks done and the obligation to live in a dormitory with other boys. I had to cover all mandatory costs associated with my operation in the company from my salary. After completing my studies, I was totally financially independent. I spent four years in the dormitory, where the following conditions were strictly observed:

- Young men were not allowed to continue in the prejudices of their parents.

- We had to be financially self-sufficient and not share our wages with anyone.

- We grew up as equals.

Young men in dormitories were divided into camps, each camp was commanded by a captain. My day had a precise schedule of time. The schedule of daily work was set in such a way that all my time was maximised. I started at 5:30 a.m. with a wake-up call and a short workout together with the other students. From 7:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. I worked in the factory with a two-hour lunch break. Every day after work, I attended school from 6:00 p.m. to 9:00 p.m. My day ended at 9:30 p.m. with lights out.

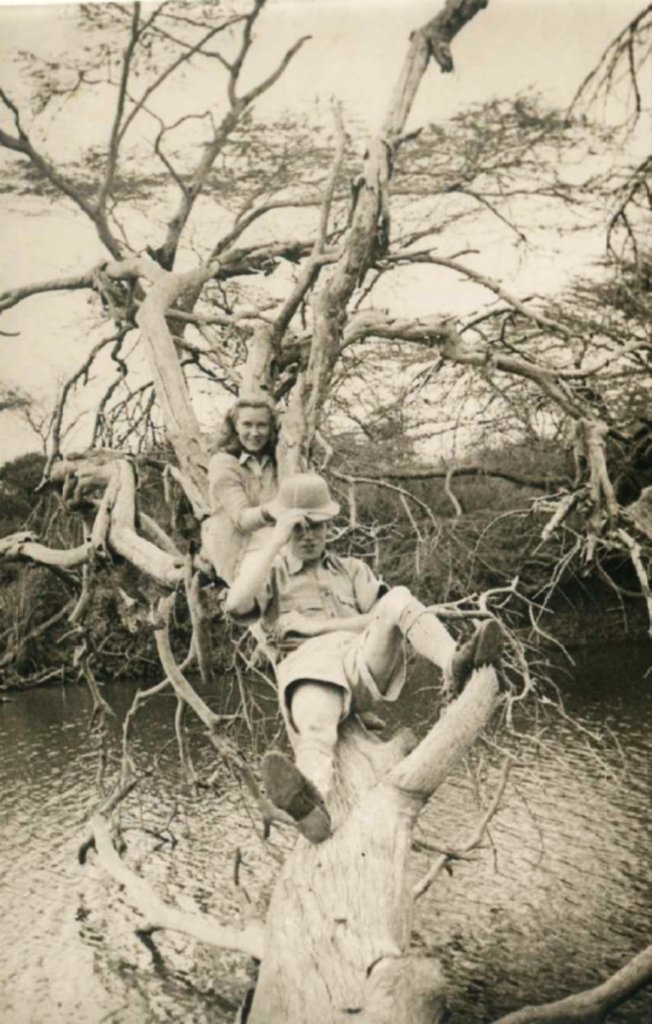

The Baťa company educated me in the spirit of a personality who will be an example to the whole society. My upbringing style had built the ability to be highly flexible, adapt to the conditions and philosophy of the company. I went through several positions from shoemaker to sales in the Baťa company. In 1939, I received an offer to expand the business of Baťa’s company in Kenya and July 26 became the memorable day when I left Europe onboard the ship heading to Mombasa. The start on the African continent wasn´t ideal though. I was arrested at the port on suspicion of being a German spy, as the ship belonged to the German Reich. I spent the next 5 days in Fort Jesus Prison in Mombasa in total uncertainty. Thanks to the successful negotiations of the Czech ambassador and the management of Baťa’s company in Kenya, I was freed and my career in Nairobi could begin. I worked as part of the sales team for Kenya and the surrounding East African countries. Toward the end of World War Two, Baťa made me an offer to relocate to Rhodesia, which was perceived as one of the main economic centres of Africa. In January 1945, I moved to the city called Gwelo (now known as Gweru) and worked at the company’s headquarters as a junior accountant. Baťa Gwelo was founded in 1939 and up until 1970 the main management positions were held exclusively by Czechs. Therefore, at most meetings, I spoke my native language much more than English. The company was one of the pillars of the country’s economy. I enjoyed the social life, became a member of Sokol (gymnastic society) and member of the Czechoslovak Club. In the same year, I met my wife Edna, who was born there and had both a French and Dutch background. Together, we moved back to Nairobi in 1946 and I was named chief accountant for Central, East and Southern Africa.

In 1947, I took my wife and our first son on holiday to Czechoslovakia. However, upon arrival, I was unexpectedly called up to complete compulsory military service. Therefore, my leave was extended to 10 months. My wife had to learn the language to communicate with my Czech family. She began to learn how to cook Czech food and studied Czech culture. After completing my military service, we returned to Gwelo, continuing my career as chief accountant and deputy director of the company in Rhodesia. Also in 1966, 1969, 1972, and 1975 I returned to Czechoslovakia to visit my relatives and to introduce my three sons to my old country.

My last dream of establishing another factory finally came true

I retired in 1978, however the Baťa company trusted my work ethic so much that they offered me a new position soon after to assist in the establishment of another factory in South Africa. So, I became a member of the start-up team for this new business development opportunity. I accepted this offer and moved to South Africa. My last dream of establishing another factory finally came true.

Unfortunately, František Jakubec passed away only a few months later, on March 26, 1980, due to a severe illness. It was quite common for other descendants to continue their Baťa loyalty and work in Baťa companies. It was no different for all of František´s three sons. From an early age, they were part of conversations about business at meetings with family friends, which made the business inscribed in their soul. The two older boys, Frank and Paul, worked in various Baťa entities in Rhodesia, Paul even moved between various Baťa locations in South Africa, Botswana, Kenya, and Uganda. The youngest one, Brian, however had ambitions to start a career in another segment of the business, namely IT. Inspired by his father’s honest work and his courage to take the risks of entrepreneurship, Brian worked his way up to top management positions with companies in South Africa, the USA, and Dubai. He lives in Slovakia now.

Dean Harris

I’m trying to find frank jacobec junior who I last saw in Rhodesia about 1973