Milan Vítek

I was born on February 7, 1927 in Královské Vinohrady district in Prague. In the early 1930s, my family moved to Karlín, where at that time my father and his brother Antonín owned a car construction company “A+B Vítek”. After five years of primary school and graduation from high school in 1946, I was accepted to the Faculty of Law of Charles University. I was active in the student clubs there and organized agricultural youth brigades. However, the Communist regime prevented me from completing my studies. In the spring of 1948, shortly after passing the Roman law exam, I left Czechoslovakia to avoid certain imprisonment because of my activities in the People’s Party, in the Všehrd student association, and also because I co-organized a march of university students to the Prague castle in support of President Beneš not to give in to Communist pressure. Naturally, it was already too late, and the march ended infamously with arrests. A bit later, I ignored the summons to appear before the “purification commission” at the faculty and knew that I had to leave the republic. I hoped that I would return with the American army within two years. I naively believed that the superpowers would not allow a second Munich treason.

In August 1948, the International Refugee Organization took over the administration of the camps

I crossed the state border into Germany in early May 1948 and spent four months in the Wegscheide refugee camp in Bad Orb. Count Karel Parish, the owner of huge estate in Žamberk region, who later owned farms in Canada and incidentally became my father-in-law, was elected head of the camp. Parish sought out his friend, Colonel Wood, who was the commander of the military police in Frankfurt. Thanks to him, the camp residents received enough food. In August 1948, the International Refugee Organization took over the administration of the camps, Wegscheide was closed, and I headed for the “student” camp Arsenalkaserne in Ludwigsburg. There, I was even able to continue my law studies and attend lectures at the provisional Masaryk University College, founded and led by professor Vratislav Brdlík, our leading expert on national economy.

In the meantime, I had obtained a visa to Canada. I signed a one-year work contract as an agricultural laborer. I had a choice of mines, quarries or agriculture. They moved me to Bremerhaven and on April 23, 1949, I arrived in Halifax onboard the ship SS General Leroy Eltinge, along with one hundred and thirteen other Czechs and Slovaks. They transported us by train to a camp in the suburbs of Toronto, which served as a training center for Western spies during the war. Farmers from Quebec and Ontario came there and selected people for work. The salary was between 40-50 dollars, board and lodging included, per month. Surprisingly, the farmers were much more interested in our religious belief than in our knowledge about agriculture. I must mention that the Canadian labor office representatives were extremely polite and helpful to us. I worked on four farms in total and exactly one year later, in April 1950, I started working as a laborer in a Toronto ladder factory. However, it was only seasonal work. In September 1950, I began my “career” as a carpenter for Philips in the Leaside district. At the end of December, I got married and a year later our only daughter, Elizabeth Marie, was born. At that time, I was already fully active in the Czechoslovak National Association of Canada, I played the piano in the Sokol dance orchestra, I became the first organist of the Czech Roman Catholic parish of St. Wenceslas. I also got involved in political activities and together with the son of the Protectorate Minister Havelka, we established a branch of the National Democratic Party in exile.

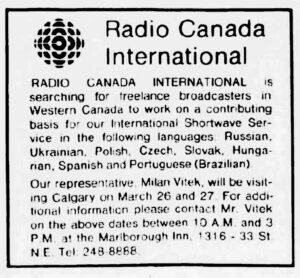

Over the course of several years, I worked for various companies before joining Mr. Williams’ Custom Sound & Vision company in the fall of 1954, first as a hi-fi technician and later as a salesman. I continued in this profession for two more companies before, at the end of 1962, I won a competition to become an editor in the Czechoslovak section of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) in Montreal. I remained there in various capacities for a total of twenty-five years. I prepared and edited texts for the air, translated, broadcast, accompanied Czechoslovak visits and delegations on trips to Canada, and recorded hundreds of interviews. Everyone knew that I was a political refugee – Canadians, as well as members of the official delegations from Czechoslovakia, i.e. athletes, artists, scientists, and Communist functionaries. However, I never compromised myself or my strong political convictions. In 1977, I was appointed director of Canadian broadcasting in eight languages of Central and Eastern Europe. It was sure that the people of the countries in this region knew best how they were doing. They didn’t need to hear that from a Western radio. On the contrary, they were curious about how Canadians lived and what they did. The fact that we were successful with listeners in Czechoslovakia is also evidenced by the later establishment of the Society of Friends of Canada. For four years (1983-1987) I served as deputy program director of CBC, working closely with the Voice of America and Radio Free Europe. I retired in November 1978 but continued to work.

I was very pleased with the academic rehabilitation at Charles University, which awarded me an honorary doctorate in law

After the Velvet Revolution, I was very interested in what was happening at home. In 1992, I became an advisor to the general director of the Czechoslovak Radio, Jiří Mejstřík, and even advised the Polish Radio. I also visited Prague in the following years quite often and was available for advice close at hand to the Czech Radio Council. In June 1993 it was not possible to select a new Director General for the radio from thirteen candidates, so I temporarily held this chief position. Moreover, the Canadian ambassador at that time was my old friend Alan McLaine, long-time director of the Soviet department at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Ottawa. I was very pleased with the academic rehabilitation at Charles University, which awarded me an honorary doctorate in law. After such a long time, it was a great satisfaction. At the same time, I was aware that my activities abroad had a negative impact on my parents and sister, who had been bullied by the regime for a long time. I never kept a diary, I always relied on my memory, which unfortunately is not what it used to be.

Milan Vítek died in Toronto on May 14, 2014. Three years earlier, he provided a brief account of his life to an employee of the Embassy of the Czech Republic in Ottawa, Mrs. Miloslava Minnes, to whom we would like to thank. Unfortunately, we were unable to find any high-quality photographs of Mr. Vítek, for which we apologize to our readers.